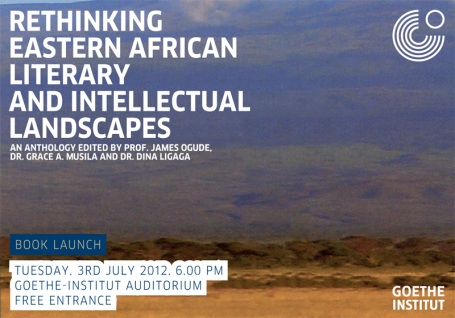

Rethinking Eastern African Literary and Intellectual Landscapes is a new book, a collaborative effort between East African academics, writers and thinkers. The book launched at the Goethe Institut in Nairobi on the 3rd of July, 2012.

While introducing the book, Dr. Tom Odhiambo reaffirmed the urgency and need of such endeavours by East African thinkers. He lamented the baleful disregard of arts and humanities by university administrations in Kenya where it frequently occurs that academics are unable to secure funding for their projects ‘because their work is not scientific enough’.

Dr. James Ogude explained how the book was conceptualized; it is an attempt at finding ways to re-energising intellectual scholarships within East Africa.

“We may work with the world, but it is necessary to have our own local interventions,” Ogude said. “A society that relies on foreign voices to tell its own stories is a dying society.”

Ogude recounted the intellectual climate of the 60s. “We have never looked back at that era and captured the intellectual traditions,” he said and illustrated how Ngugi and others led the intellectual revolution. “This book attempts to reassert East Africa as an important site of culture and intellectualism.”

Ogude shared details of his recent meeting with Ngugi. “Ngugi and I reminisced on those days gone. See, back then, we never quite realized the contribution of scholars in the region. And then Ngugi asked me where in Nairobi the book was to launch. He laughed when I told him, said we are still relying on the patronage of former colonial masters. What happened to our own homegrown spaces? Why do we never take the initiative?”

Ogude explained how received theories (from the west) inflected the manner of perception of our own experiences by reversing the hierarchy of our intellectual values. This is what Ogude terms as ‘The African Urgency’, one that needs to be addressed.

“The humanities are the crucible of society. We can produce technocrats, but society needs its thinkers.”

Dr. Godwin Murunga criticised the learning of African Studies as a distinct, monolithic unit. “I do not understand why, in this day and age, a university in Africa would teach African Studies. Have we, all this time, been studying aliens?” he asked. “Why must we depart from history, from literature, from art, and look for Africa in a place called ‘Africa Studies’?”

Murunga spoke of the global politics of education and the bearing of one’s academic affiliations to one’s global visibility (a severe reality that makes African scholars virtually invisible). He also spoke of the pitiful internal dynamics of our own institutions, the astonishing ways in which our universities self-annihilate.

Dr. George Ogola discussed the politics of the exiled African intellectual. He explained that diasporic intellectuals are often dismissed as inauthentic precisely because of their absence, a criticism that ignores the moral and material realities. Intellectual traditions do not follow linear trajectories, and many intellectuals and thinkers are so because of the anxieties of exile.

Ogola explained that the book is important due to its decolonisation of modernities, and due to the fact that the book not only focuses on Kenya or Africa but transcends it.

“This book is both historical and contemporary,” he said. “It redresses concerns of thematic insularities. It questions, for example, not just the patriarchy of European imperialism, but of African nationalism. What is the place of the woman as producer of intelligent output? Whose intelligent traditions are we engaging with, and where is the place of the woman in this?”

After a brief musical interlude during which the gripping Makadem performed, the audience was allowed to field questions. One particularly resonating one came from someone that spoke heatedly of what he termed as ‘positive primitivism’.

“The past is always better than the present,” he said, levelling his criticism against the intellectuals who looked back at the 60s and 70s through rose-tinted spectacles. “The revolution of the 70s meant to bring African voices at the centre of departments, and to put English aside. What then would have been the logical conclusion?”

He explained that in his opinion, African voices are best heard in African languages. In Kenya, there is a larger body of work in Swahili today than there was in English in all of the 60s, 70s and 80s combined.

“Why then do we say that literature has died? Back then, we were unhappy about expressing Kenyan voices in foreign languages. What we hear now is a dominant story, one expressed in English. Does it mean that if it a voice does not speak in English then it does not exist?”

In answer to this, Ogude expressed satisfaction at the growing body of work in Swahili and other local languages. He warned, however, that it will come to naught should this work be ignored by intellectuals.

“We need to engage with these works,” he said. He went on to address the criticism against such ‘positive primitivism’ with regards to the nostalgia of the 60s and 70s:

“Makerere, the University of Nairobi were functional institutions back then. We need not sweep realities under carpets. We must face ourselves, demand answers from ourselves. It is inevitable that intellectualism will plummet if student bodies increase exponentially without concomitant increase in academic resources. What we are seeing right now is a phenomenon where our students do not go through university, but university goes through our students!”